Trump suggests Chinese migrants are in the US to build an ‘army’. The migrants tell a different story

It was 7 a.m. recently on a Friday when Wang Gang, a 36-year-old Chinese immigrant, jostled for a job in New York City’s Flushing neighborhood.

When a potential employer pulled up to the street corner, Wang and dozens of other men swarmed around the car. They hoped to be chosen to work on a construction site, on a farm, as a mover – anything that might pay.

Wang had no luck, even though he waited another two hours. It would be another day without work since he illegally crossed the southern U.S. border in February.

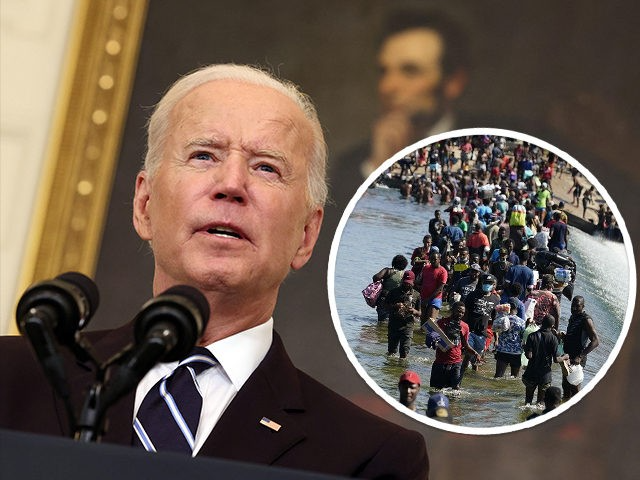

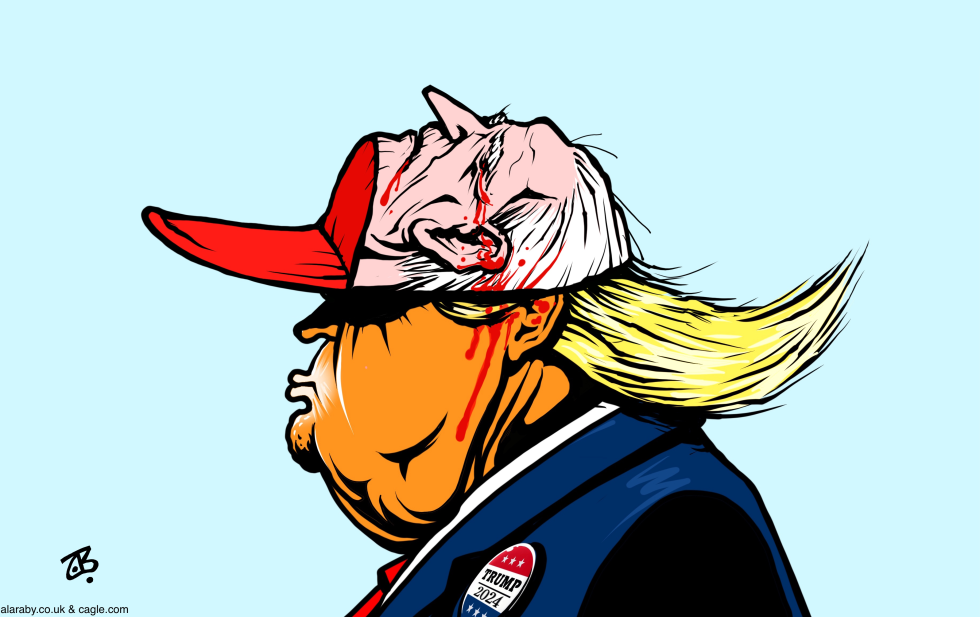

The daily struggle of Chinese immigrants in Vlissingen is a far cry from the image of the former president Donald Trump and other Republicans have tried to portray them as a coordinated group of “military era” men who have come to the United States to build an “army” and attack America.

Since the beginning of the year, as Chinese newcomers adjust to life in the US, Trump has alluded at least six times to “fighting age” or “military age” Chinese men and suggested at least twice that they are building a migrant army. shapes were. .” The topic of conversation also appears in conservative media and on social platforms.

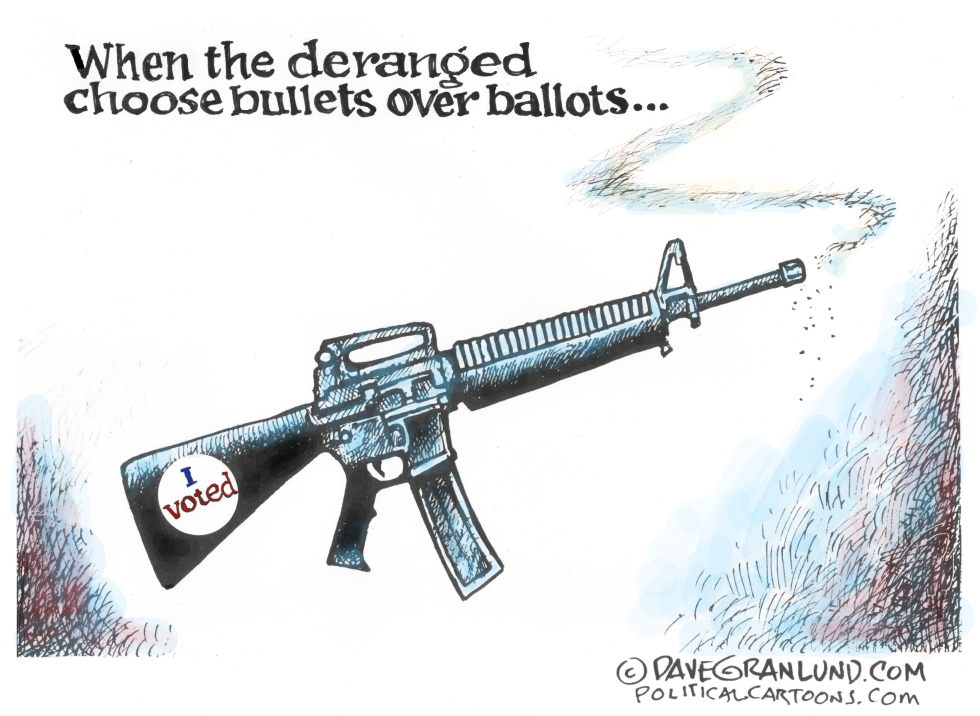

Asian advocacy groups say they worry the rhetoric could encourage further harassment and violence against the Asian community, which has seen more hate incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Wang, who spent several weeks traveling from Wuhan, China, to Ecuador to the U.S. southern border, said the idea that Chinese migrants were building an army is “non-existent” among the immigrants he has met.

“We came here to make money,” he said.

Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell last month called the Chinese nationals “economic migrants.”

Sapna Cheryan, a professor of psychology at the University of Washington, said the claims about Chinese migrants – made without evidence – build on widespread stereotypes that Asian people do not belong in the country.